🛑A couple of things before you start reading🛑

⚠️This post comes with a content warning. I will be talking about school shootings. If this isn’t something you can or want to read, please skip this and wait for tomorrow’s post. See you then!

🗓️Speaking of which, newsletters will resume (regularly) on Thursdays again.

***

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

—T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men”

Nearly 20 years ago, I sat in a physics class in Dawson College desperately waiting for it to end. When I was finally dismissed, I pulled out my phone and saw numerous missed calls from a friend waiting in the cafeteria. Then came the incoming call from her. Before I could say anything, all I could hear was “Get outside.” I asked what was wrong, but she kept saying, “Get out of the school.” Walking down 10 flights of stairs, I kept thinking this was a prank. When I stepped outside, I almost tripped over a student on the ground. When I looked up, there were the police telling me to do the same.

***

The year before, I had watched Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003) for the first time. It’s a very slow record of the day and I remember being lulled by its pacing. High school students walk from class to class, completely unaware of what’s to come. As Eric and Alex, the stand-ins for Columbine shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, make their way to the school armed, we watch as their classmates struggle with body image in gym class, bulimia, parents or getting to school on time.

The violence doesn’t energize the film either. Two school shooters stroll around killing people while Beethoven’s “Für Elise” plays in the background. This is a stark contrast to the violence displayed in action movies, where gunshots are thunderous and tension is only released when a bloodbath begins or bombs detonate. There is, always, a clear hero and villain. In Van Sant’s hands, the violence isn’t sensationalized and the real culprits aren’t quite clear either. As Eric and Alex target their classmates, there are flashbacks to the boys being isolated and bullied, buying guns online (easily), and playing violent video games.

***

While they share the same name, Van Sant said he was not inspired by Alan Clarke’s 1989 short film. But like its 2003 namesake, Clarke’s Elephant pulls from real-life events in Northern Ireland during the Troubles1. For 38 minutes, a camera follows a gunman around as he kills 18 people in Ulster. There is little dialogue. We get no insight into his motives, rationale or mental health. The only context is the title, an allusion to Irish writer Bernard MacLaverty’s description of the conflict as “the elephant in our living room,” which “[n]obody mentions it because it’s just so enormous.”

Different stories are circulating online about how Van Sant chose to title his film. Some sources claim it was a tribute to Clarke. Others say it was about the parable of the blind men and the elephant, where each man draws a different conclusion based on which part of the animal they touch and describe. In his hands, we get multiple viewpoints of a school shooting, all drawing different conclusions, and muddling what we believe is right and wrong.

***

In the aftermath of a mass shooting, reporters will broadcast a timeline of events. I’ve always thought about the significance of this framing because chronology rarely clarifies a motive. With hindsight, reporters can cast a long foreshadow over the day’s events, imbuing even the most mundane tasks with doom. These timelines activate a fear response, unleashing a series of torturing what-ifs.

How many other people did they cross before they opened fire?

What if they went somewhere else?

What if this happened at my school?

To my kids?

What if?

It was reported that the Dawson College gunman was bullied in high school. He played violent video games. He posted photos of himself online with semi-automatic weapons, many of him pointing a gun at the camera, forcing the viewer to stare down its barrel. The morning of the shooting, he was caught on video scoping out other schools before he settled on this one, a site completely removed from his past and pain. Then he walked into the school cafeteria, the same one my friend was sitting in and opened fire.

The aftermath was broadcast throughout the day. Students crying. Others on stretchers in front of ambulances. Terrified classmates dodging reporters as they were running to safety. Many people were injured. Some were held hostage. One was brutally killed. And the gunman died by suicide.

***

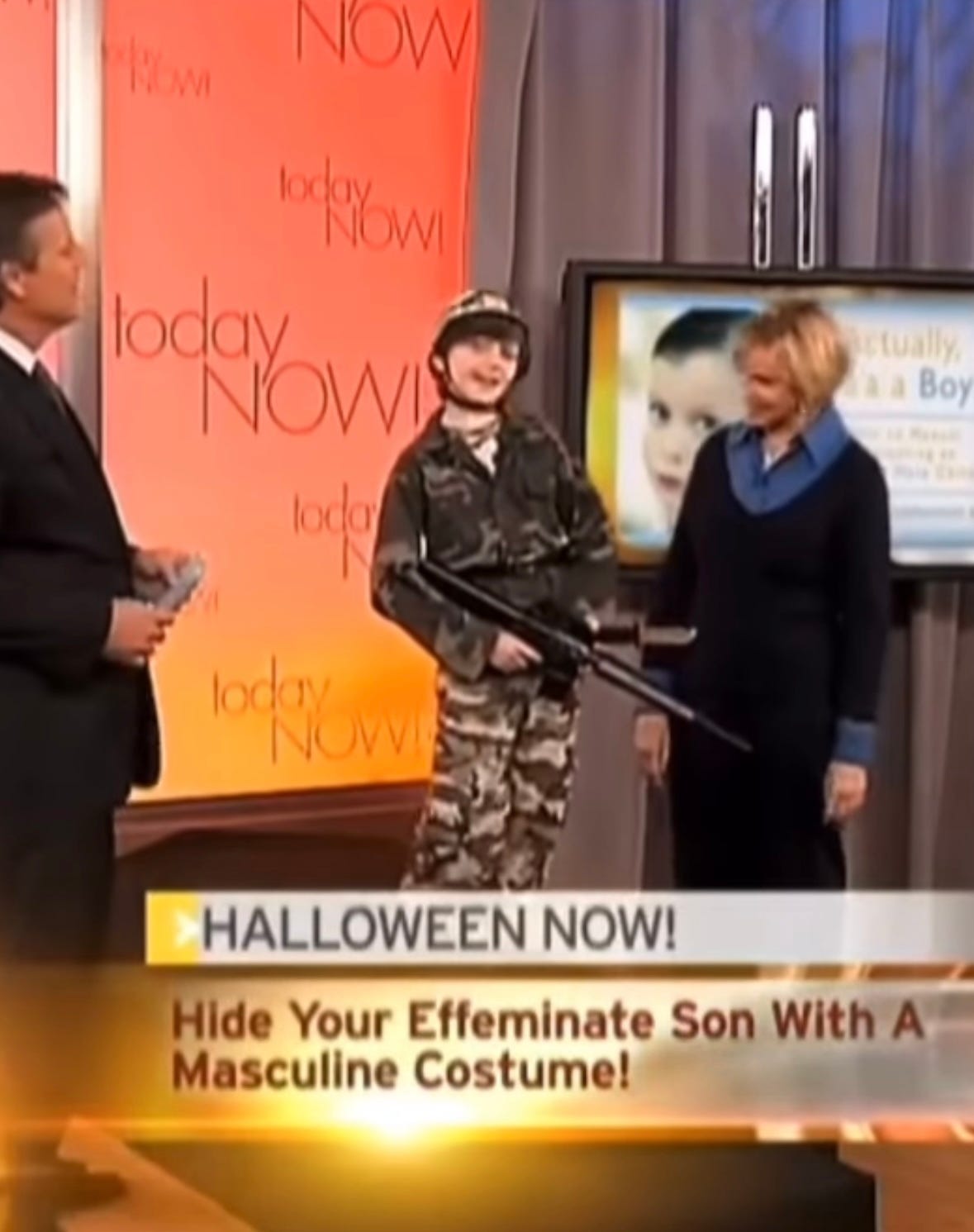

My issue is that the day in the life of a mass shooter never goes back far enough. So quick to shape a story out of senseless violence – and so quick to get ahead of it – reporters look into mental health, social status and the purchase date of weapons. The analysis, if that’s what it is, is so predictable by now. Or maybe there have been far too many mass shootings.

But what if the interrogation went further? As in:

Who is constantly supplying and providing weapons?

What kind of deals are being sealed to enable this? Who taught this person that this was how you dealt with problems?

Who showed them that to gain control, you had to massacre other people?

Where did they learn that the only way to be a man was by playing god? Or pointing a gun at someone?

Why aren’t guns insured?

Who pays for the victims’ medical bills?

***

As British academic John Sutherland noted in a Guardian column from 2003, everyone was alluding to an elephant in the room. A month before Elephant premiered at Cannes, The White Stripes had released their album Elephant, with the first single being “Seven Nation Army.” A month before that album’s release, the United States invaded Iraq.

News channels reporting on mass killings air segments with special guests who blame violent video games and movies by rote. And yet, these are the same channels broadcasting live from warzones or selling everyone on a war because of fictitious weapons of mass destruction. What if people are simply reflecting the violence and terror they all see in the real world? The massacres outlined in history books and memorized for exams? The world leaders who prioritize funding wars over healthcare and education? The 6 o’clock news is a constant reminder of how much war, like dead children or teens, has been normalized. Civilians and bystanders aren’t real people with lives but casualties or collateral damage.

***

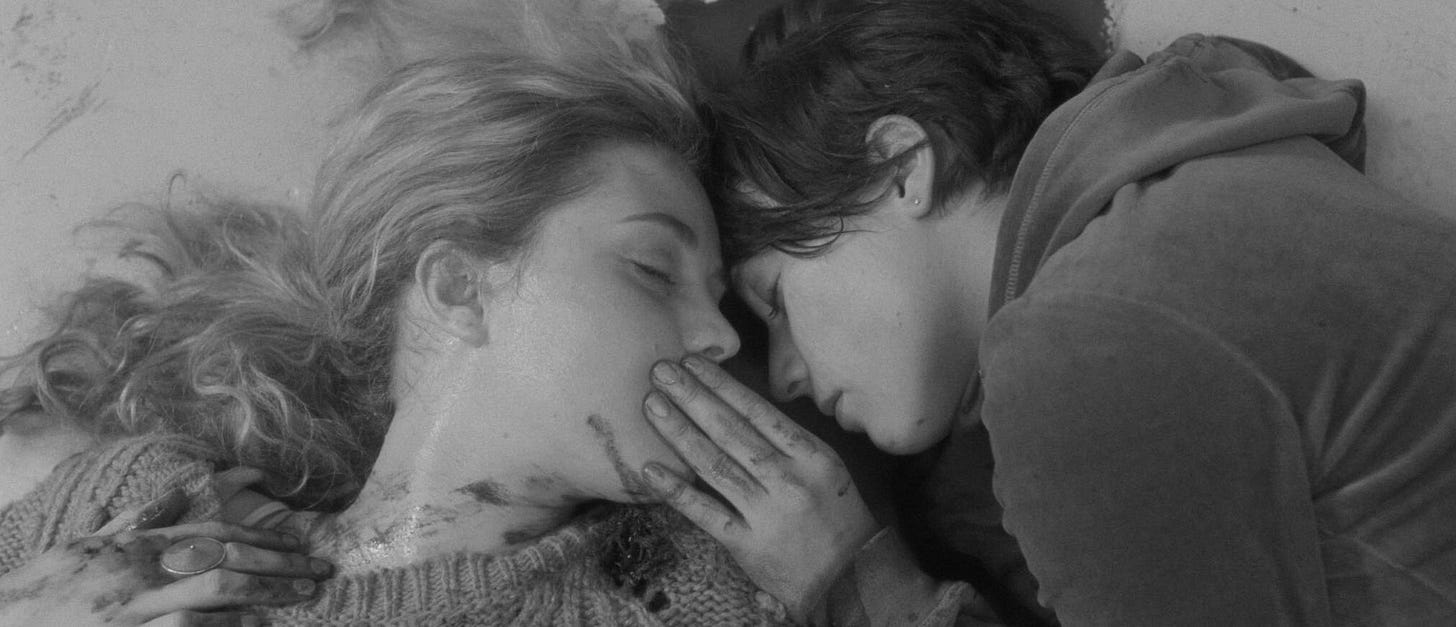

One of the characters we meet in Elephant is spared. John (the blonde boy being kissed on the movie poster) runs into Eric and Alex in full gear outside the school. When he asks them what they’re doing, Alex tells him, “Get the fuck out of here and don’t come back.” In a panic, John starts pleading with people not to enter. When I rewatched Elephant recently, I noted the “palpable sense of fear” Peter Bradshaw described back in 2003. But this only came from my perspective as a viewer.

Like anything life-changing, a day is just a regular day – even a boring one – until something happens. As with anything that impacts survival or quality of life, we leave it to fate, luck or timing. Preventable deaths are dismissed as accidents, terrible luck, or being at the right place at the wrong time.

If there is one thing that binds victims to their attackers, it is that the onus of responsibility falls on the individual. That could mean thinking on your feet, a higher power intervening or running active shooter drills. On the flip side, you are a bad apple, trouble, a lone wolf, an outsider.

***

As my friend sat in the cafeteria waiting for me, all she could remember was a commotion. Thinking it was a prank, she thought nothing of it until a security guard shoved her under a table. She didn’t remember when or how she got out. She barely remembered calling me. By the time the gunman had entered the cafeteria, two police officers, on a “routine drug call,” had cornered him after watching him shoot students near the entrance. His plan had been foiled before he could start.

The thing about guns is that they do enough damage in very little time. For months, my friend suffered from panic attacks whenever she heard loud, sudden noises in crowded areas. We reflected, over and over again, on our timing. What would have happened if…

***

Denis Villeneuve’s Polytechnique, based on the 1989 femicide in Montreal, doesn’t just depict the brutal slaying of 14 women, but the emotional and physical toll it takes on its survivors: with recovery comes survivor’s guilt and remorse. The film is often celebrated for its realism, for bringing together the many POVs impacted before, during and after the shooting. But I keep wondering about the details these films have to fill in — mainly the carnage — for a fictional adaptation. As much as we’re given every detail about the gunman and the events of the day, we’re never confronted with what bullets do to the body. And what series of events, policies, back end deals get us here time and time again? The bodies are always hidden and so is the money trail. I wonder what more people would do and who they would advocate for if they saw just how little is left behind.

In an effort to get us back to normal, the school closed for a few days so a crew could clean up. They filled bullet-ridden walls with plaster and painted over them. Administrators wanted everything cleared and repaired before we came back. And when we did, the effect was jarring, like nothing had happened. Like we had imagined it.

Camera crews parked outside snapping photos of students entering the school. It helped to counter the terrifying images of us running out, making a neater, more hopeful ending.

***

Three days after the shooting, then-prime minister Stephen Harper was trying to abolish the gun registry in Canada. A classmate who still had a bullet lodged in his head, wrote a letter to him pleading not to do it. He never got a response.

***

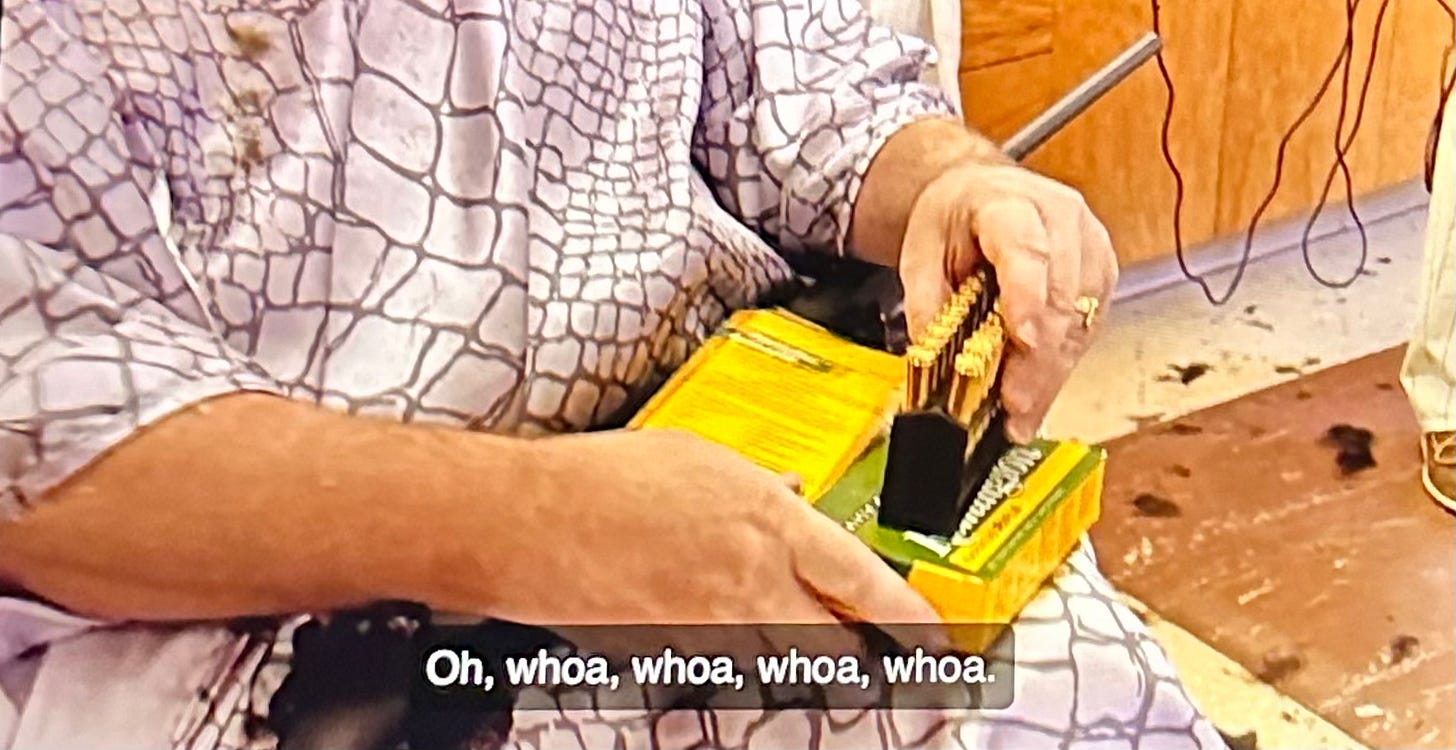

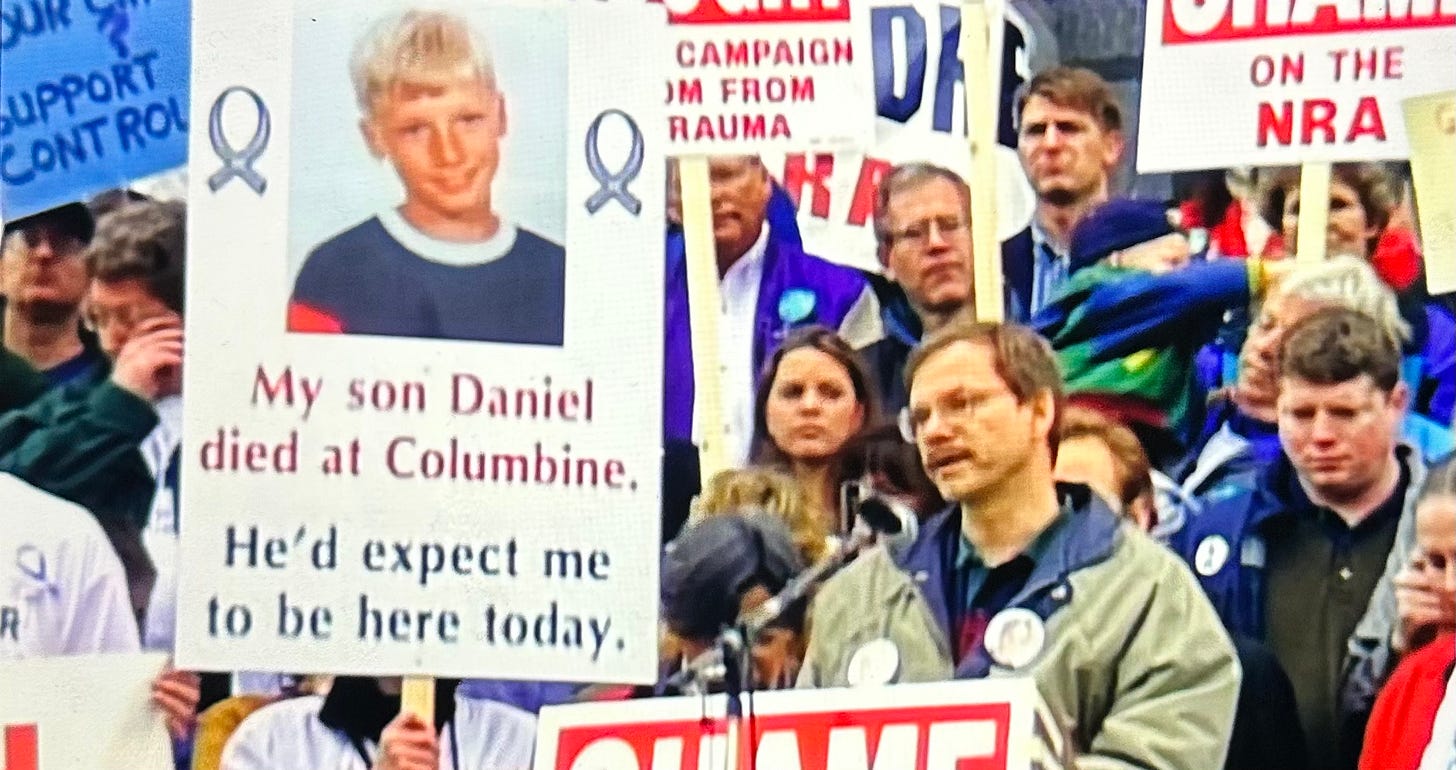

What do bullets do to bodies? And why are photos never released? I remember a scene from Bowling from Columbine when Michael Moore shows Charleton Heston, a major gun advocate and then president of the National Rifle Association, a school picture of a recent shooting victim. Heston walks away from him.

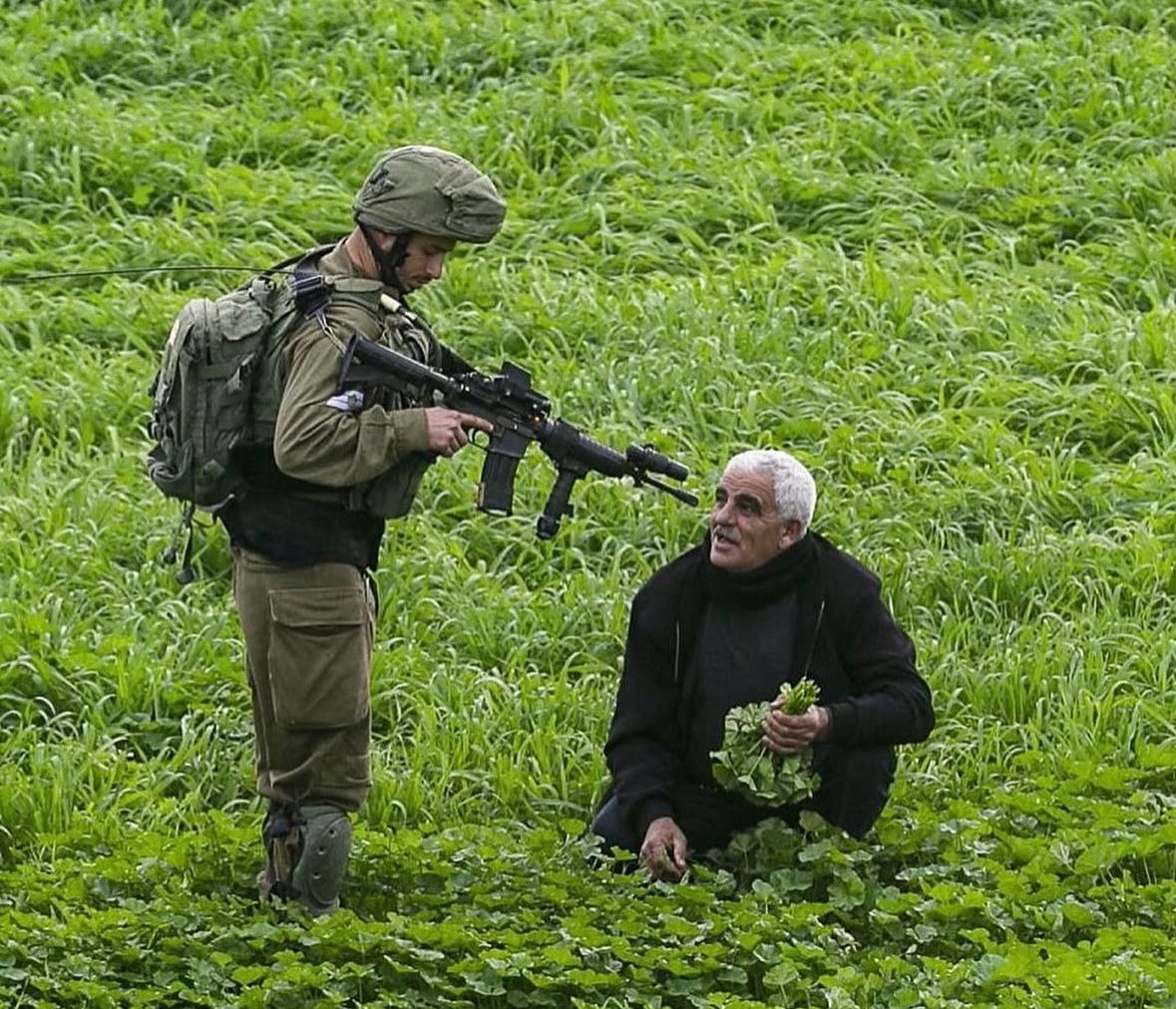

It seems now that a great distance is put between a weapon and its victim. And yet, this hasn’t lessened the damage. We do the same with language. People, especially children, become casualties or targets, all rounded up in a death toll. The same goes for Gaza, where people are obliterated with drones. We watch Palestinians carrying what’s left of loved ones in small shopping bags. For the last few months of 2023, we saw what our government and leaders enabled, funded and supported. In Iraq, we never got images, but a rough estimate (now up to 200,000 casualties). And yet, as we speak, more weapons are being shipped out. Death and devastation are justified and celebrated on every platform – even during a presidential election – as signifiers of progress and freedom. Or, as Kamala Harris recently put it: “I have a Glock.”

***

Back then, it was easier to move on without finding the right words to express grief, fear, or loss. And all that’s left after everyone moves on is a Wikipedia entry. What I do know is that the shooting at my school came after a long list of others. And the list is still growing.

A 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland between Irish nationalists (who wanted to leave the United Kingdom) and loyalists (who wanted to stay). This is an oversimplification, especially when it comes to British colonialism/rule, Ireland, conflicts and resistance movements.