Doug Liman’s Go is often compared to Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction because of its narrative structure (non-linear) and one scene in a greasy diner. But unlike Go, Pulp Fiction is a morality play, where characters, according to Tarantino, “...make the choices that they make and they pay the price…or they live to tell the tale because of those choices.” So much more happens in Pulp Fiction after someone stops to reflect — at a red light, before an escape or for a bathroom break.

Go, on the other hand, is a Christmas movie with no red in sight. There is no time to reconsider; the action is happening before anyone has thought anything through. There is no better judgment because the light is always green.

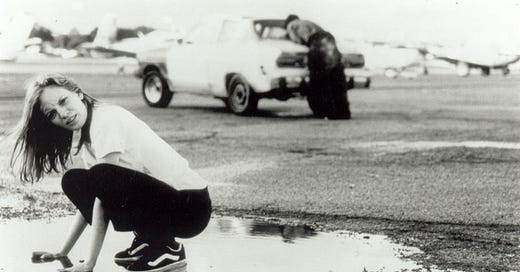

Screenwriter John August wasn’t thinking about Pulp Fiction when he started writing the script. He recently told GQ that he was in a Ralphs on Sunset Boulevard on Christmas Eve, wondering what the young grocery store clerks did after they clocked out. His version of their story begins with Ronna Martin (Sarah Polley), who is bagging groceries for a customer. The mother is reviewing the receipt; balancing a baby on her hip; and instructing Ronna not to pack bleach with food items.

What do you do when you’re underpaid to serve customers? Ronna defiantly wraps the bottle of bleach in a plastic bag before packing it in with peanut butter and cans of SpaghettiOs. “Don’t think you’re something you’re not, I used to have your job,” the customer informs her. “Look how far it got you,” Ronna deadpans. Unlike Pulp Fiction, Go never depicts a crisis of faith, but identity.

***

Who am I and how did I get here? comes to mind when things take an unexpected turn. It’s an admission that at some point in your life, you went down a road with promise and the start of a story. Now you’re stuck and barely recognize yourself. Life decisions can have momentum, but not every one of them propels you forward.

In his version of Go, August’s screenplay opens with Ronna Martin bleeding in a ditch after a night of playing drug dealer. What got her here? She clocked out of a 14-hour shift, where a coworker stopped and asked if she could cover him so he could go to Las Vegas. Desperate for cash to avoid an eviction, she accepted while he fronted her the rent money. She then buys 20 hits of ecstasy for 2 actors with that cash advance. Not only was she set up but she escaped. And now she’s managed to survive a hit-and-run. She can’t move her legs or help herself up, but “[d]espite it all, there’s a smile of perverse joy to her face, like she’s just remembered the punchline to a favorite joke.” Is she running through the steps that got her here? Probably not.

Doug Liman’s cut starts instead with a monologue from Claire Montgomery (Katie Holmes):

“Do you know what I like most about Christmas? The surprises. I mean, it’s like, you get this box and you’re sure you know what’s inside of it. You shake it. You weigh it. You’re totally convinced you have it pegged. No doubt in your mind. But then you open it up and it’s completely different. You know. Wow! Bang! Surprise! It’s kind of like you and me here. You know? I’m not saying it’s anything it’s not. Come on. This time yesterday…who would have thunk it?”

Despite the crash now, think later mantra of this film’s central figures, some people like Claire offer great advice. But she is a voice of reason talking to a wall. She is so honest that she’s a buzzkill and is subsequently left behind as collateral for the drug dealer.

Everyone around her assumes a false identity: Two closeted actors sit through an awkward dinner as a fed tries to recruit them into an MLM. Ronna moonlights as a drug dealer, pushing fake ecstasy at a Christmas rave. No one here is interested in redemption arcs, better decisions, or higher ground; they’re looking for a second chance to fuck up. Go is underrated and forgotten because most audiences are primed for a tidy tale of personal transformation and self-determination. Instead, they get 18-year-olds desperate for change but doomed to fail.

***

I first watched Go at the end of 2020, when talk of minimum wage and working conditions drove every form of content creation. Instagram was becoming a mall. Recruiters were posting tips for cover letters and acing job interviews. So many people were transitioning out of service and retail industries for the promise of something better. Everyone was rethinking their purpose, work/life balance and the four walls around them. All they had was a lockdown order, CERB cheque, and a dream1. Instagram and TikTok reflected this to everyone by boosting a constant stream of redemption arcs: before and afters, GRWMs and life updates. Things seemed possible because there was no looming recession or no inflation. Groceries were affordable and it was an employee market. Everyone was manifesting – not chasing, but attracting. What could they lose?

Very little in Go, like life, ever changes. Maybe that’s what Ronna is laughing about in the ditch. Neither August nor Liman ever offer explanations or justifications for who people are; no background information is offered to make them relatable or explain why they are the way they are. No one is transformed. Ronna wakes up in a hospital and gets back to work. The only promise of change isn’t anything different, just a new set of plans: What are they doing for New Year’s?

The promise of crypto or drop shipping.

rewatched this recently and i forgot how brutally cynical sarah polley's character and the movie's sensibility was, so much so that it was refreshing—that crash now, think later as you said