Maybe she’s born with it…

Notes on Death Becomes Her, the cult of youth, and playing against type.

“The way she handled her image recalled the same attempt at effacement, restraint, extreme limitation. She had given one photographer the exclusive right to take her picture, and he was supposed to hand over to her the contact sheets and their negatives, and any slides, as soon as they were processed and before he had even seen them. She dumped them pell-mell into her bag, where she also kept a small loupe and, as soon as she was alone, she studied them with a mixture of fear and greed, destroying the majority of them, marking the contact sheets, scratching out the corresponding negatives with her nails or the point of a needle, and bending the slides.”

— from Hervé Guibert’s “Betrayal” in Ghost Image

In 1989, Meryl Streep starred in She-Devil, her first comedic role on screen. She played Mary Fisher, a best-selling romance novelist who lives in her own world. She cuts a fine figure in “little pink pill” hues, drives up to her secluded (and pink) mansion in the Hamptons, and offloads ritual maintenance to butlers, maids, and doctors. She shaves seven years off her age and floats in her ball gown at a Guggenheim soirée.

She is too delicate and soft-spoken to manoeuvre in the real world. Why would she when her creative pursuits—30 best-selling romance novels—make people (especially in publishing) so much money? Her deadlines get pushed to suit her needs and dalliances. She’s never at a loss for friends when she’s footing the bill. Every person and obstacle moves out of her way. Someone like Mary doesn’t need to balance a cheque book or consider the marital status of lovers. She can be flighty, narcissistic, vain, and completely out of touch. Consequences simply transmute into praise and capital.

Mary will eventually be the center of a revenge plot, but her public decline leads to a favourable transformation. She rebrands herself as a high-minded author in search of truth instead of titillation. The serious and cerebral Mary is more Meryl’s speed. (Even though the film was panned as “limp,” by critics, she was still nominated for a Golden Globe.)

The release of She-Devil preceded a major medical development. Oculinum (botulinum toxin type A) had finally earned FDA approval, meaning that ophthalmologist Adam B. Scott could treat patients suffering from strabismus (crossed eyes) and blepharospasm (eye twitching) by paralyzing overactive muscles.

But back in 1987, Dr. Alastair Carruthers, a dermatologist in Vancouver, and his wife Jean discovered another practical use for oculinum. Jean, an ophthalmologist, shared an office with her husband where she treated the same eye conditions as Dr. Scott. By her own account, one of her blepharospasm patients complained when her forehead wasn’t injected during an appointment. When Jean asked her why, the patient explained that when her forehead was injected, her wrinkles went away.

Jean started injecting her own elevens, and to this day, says that she hasn’t frowned since 1987. Five years after their discovery, Jean and her husband published a paper suggesting that oculinum, which by then had been renamed Botox, could be used for cosmetic purposes. It was around this time that youth-obsessed Madeline Ashton, played by Meryl Streep, tugged at her face in Robert Zemeckis’ Death Becomes Her (1992).

“I got a call from [Robert Zemeckis] saying, ‘What would happen if a woman fell down a flight of stairs and her head got turned around 180 degrees?’ And I just said, ‘So we’re not doing Houdini are we?’ and from there on we took off.’”

– Death Becomes Her visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston

Robert Zemeckis (Back the Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?), known as a “whiz kid of special effects,” liked to do things that have never been done before. He wanted a woman to fall down the stairs and then confront the man who pushed her without realizing her neck was broken. To do this, he hired Amalgamated Dynamics and Industrial Light & Magic (special effects for Terminator and eventually Jurassic Park), who organized three shoots for that scene alone. Meryl, in turn, had to perform in a blue bodysuit in front of a bluescreen. It took a careful combination of matching and moving her head to sequence a computer-generated “twisted neck” model. They even created a “headtwist” animatronic puppet to program all the lip-syncing, animation, and puppeteering. This required engineers to study Meryl’s face closely from the footage so they could mimic her facial expressions in post-production.

In an Entertainment Weekly profile from 2000, Meryl Streep vowed to never work on a film with special effects again, declaring Death Becomes Her, “My first, my last, my only.” In a film that chronicles aging in Los Angeles, where flesh is a burden, money is no object, and no procedure is too invasive, the special effects aren’t devoted to de-aging the stars. Instead, they’re used to twist and stretch their bodies, showing what damage they can sustain while their faces remain intact. Whether they’re in duels with shovels, getting pushed down stairs, or putting a hole through an abdominal wall, the bodies manage to bounce back to life.

It was, according to Meryl, difficult to channel that rage into her fight scenes with Goldie Hawn because they barely filmed with each other. They were constantly swapped out for an inanimate object, repositioned for the cameras, or reshooting a scene multiple times so that special effects could capture their facial expressions. “Whatever concentration you can apply to that kind of comedy is just shredded,” she explained. “You stand there like a piece of machinery.” But the one time they both appeared in the same shot, Meryl accidentally cut Goldie Hawn’s face with a shovel. It left a scar.

Head of visual effects Ken Ralston wanted to rely on makeup instead of animation as much as possible because according to him, “doing anything human-like, any skin, was dangerous back then.” But when Meryl struggled with the twisted neck prop, he had integrate a computer-generated neck seamlessly, because if he had to animate her face, he wouldn’t be able to replicate the subtleties of her delivery. Contrast this with Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019), which was criticized (and equally hyped) for digitally de-aging Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino, and Joe Pesci. Industrial Light & Magic was hired for this task too, and again, they shot the actors separately on special stages to capture facial movements. They did this because, according to ILM’s supervisor, “the actors wanted to be themselves” even though the 3.5-hour film bounced between timelines. This meant that multiple models and programs were created to suit each character during every life stage.

But if we learned anything from Rian Johnson’s Looper (2012)—where the face of a young Bruce Willis was grafted (with prosthetics) onto Joseph Gordon-Levitt—just because you look like someone doesn’t mean you can act like them. The digital recreations in The Irishman don’t look right in certain lighting either: the natural contours of the face don’t recede or stand out when the faces move. And everyone looks like they’re clenching their jaw.

“At that moment, I. made a mistake with her image, which in her profession was tantamount to making a mistake in one’s career: the image of the ingenue and the child prodigy with which she been launched and manipulated hurt her, and she was ready to move on, to replace it with the all-purpose image of a sophisticated woman, a mask of makeup. Makeup didn’t make her look ugly, but it made her look commonplace: all that reminded was a cold, flat image, which I cursed every time I was confronted with it in a magazine or on a poster on a kiosk.”

—from Hervé Guibert’s “Betrayal” in Ghost Image

Zemeckis said that he casted against type: the obvious one is action-star Bruce Willis playing a nebbish plastic surgeon. It’s said that when Meryl read the script, she thought that she was meant to play bookish Helen, while Goldie Hawn was destined for glam Madeline. Instead, the roles were reversed. To Zemeckis’ credit, Madeline was a nastier and even more calculating version of She-Devil’s Mary.

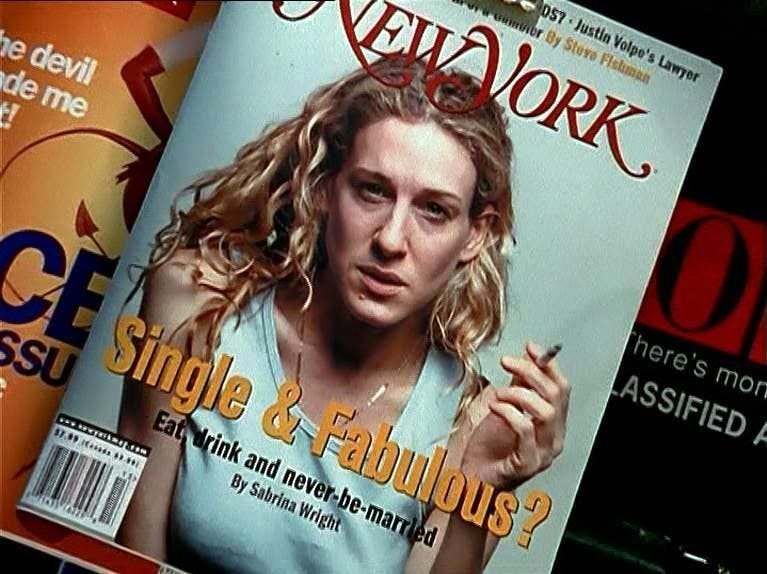

Playing against type is a common trope in comedy. But in terms of fame, it can free a referent from their signifier, allowing them to defy typecasting or even revive a failed career. Actors and public figures embody cultural values, their scandals, trends, and vices. They aren’t necessarily as good as their last role or tabloid scandal, because they are constantly captured in a moment in of their making.

When makeup and cosmetic procedures no longer work, Madeline seeks out a socialite with an anti-aging potion. Lisle Von Rhuman (Isabella Rossellini) waits until Madeline finishes drinking it to warn her to take care of her body. (“You’re going to be with your body for a long time.”) She advises Madeline to continue acting for 10 years, and then retreat from public life to avoid any suspicion. She can stage a death or suicide, but not a comeback.

What’s left out of Death Becomes Her is the state of Madeline’s career after the hands of time recede. We know that she’s washed up, but we never see her reclaim her fame. In an early trailer for the film, someone refers to her as a “big star in the 60s,” and we even see her get a call from her agent. But these scenes were cut from the final version. The potion freezes her in time, lifts her ass and tits, but never revives her career.

On the other hand, when Helen gets her dose, she gets a second chance at life. After Ernest left her for Madeline, she becomes consumed with a murder plot and completely lets herself go until she’s evicted from her apartment and checked into a mental health facility. 14 years pass and we’re at the launch party of her book, Forever Young. It’s her moment of redemption, and just as Madeline is about to leave, the crowd parts, revealing a made-over Helen. She looks like Jessica Rabbit come to life.

[It’s important to note that Jessica Rabbit was modeled after Vikki Dougan, a model and actress known as “The Back”, who was, thanks to her agent, not only made into a sex symbol, but eventually scorned for it. She had faded away until Zemeckis revived her image as Jessica in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). Notably, her tagline is “I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way.”]

We long for the delight of illusion, which is why we nail people, places, and faces at particular times. With celebrity culture, Audrey Hepburn is forever Holly Golightly, Judy Garland is Dorothy, and Elvis isn’t himself without that embellished jumpsuit. We’re taken by stories of rejected roles because we momentarily question an illusion’s efficacy: What if Shirley MacLaine hadn’t turned down the role of Holly Golightly? What if Goldie Hawn and Meryl Streep, who were originally considered for Thelma & Louise, drove off the cliff instead? Would the films be as effective and memorable?

Though botox was once for the vain, its therapeutic uses now align it with body maintenance. It’s now considered a treatment option for chronic migraines, excessive sweating, overactive bladder, and even depression. As a cosmetic procedure, it has been rebranded as preventative: Keen 25-year-olds can now, like that mysterious elixir in Death Becomes Her, freeze their face at a specific time with preventative botox. Basically, it treats the outside and the insides.

Although Madeline and Helen can live forever without aging, they still manage to die...and stay alive. Their lives aren’t devoted to looking younger, but lifelike—they spray paint a summer glow onto their corpses, paint over their shock-white irises, and touch up as they crease. Despite Lisle’s warnings, they don’t take care of themselves either. At the end of the film, as they exit Ernest’s funeral, their joints squeak and their struts are stiff. The spray paint scales off because their skin is decaying.

The older we get, the more we feel the years we’ve accumulated. Hangovers last for days. Anything can give you heartburn. And you can no longer pull all-nighters. We pour over fine lines and career goals so we don’t have to face those internal changes that come with aging. We’re seemingly punished for our wisdom.

At 19, I got sick and when I found out I had to take a pill for the rest of my life. I told a doctor how it felt like a cruel joke, a daily reminder of what had happened. He told me that eventually, everyone I know will be taking a pill for something. I was just getting a head start.

“I feel completely empty now that I’ve told you this story. It’s my secret. Do you understand?”

“And now?”

“I don’t want to have to ask you not to repeat it.”

“Yes, but now your secret has also become my secret. It’s part of me, and I’ll treat it as I all my secrets—I’ll get rid of it when the time comes. Then it will become someone else’s secret.”

“You’re right. Secrets have to circulate…”

—from Hervé Guibert’s “Secrets” in Ghost Image

You can now do more than just paralyze some muscles in your face. There are fillers, cheek and lip implants, vampire facials, liquid nose jobs, thread-lifts, and whatever customized regimen of peels, lasers, hydrafacials and injectables you choose. I don’t mind plastic surgery until a celebrity launches a skincare line and acts like it’s been their secret all along. Last week, J.Lo promoted her own skincare line while denying she’s had botox, fillers, and even facials. Instead, she attributed her trademark youthful glow to olive oil, which she’s advertised as the main ingredient in JLO Beauty.

She spent December teasing her followers about her face mask, which she alleges takes 10 years off her face. In an Instagram video, she claims the mask is better than SK-II (?!) and it’s worth $10,000 (?!?!). But as someone commented, her face barely moves in the video, meaning she’s clearly had Botox. “That’s just my face!” she responded, before plugging JLO Beauty again.

Tall tales go hand in hand with celebrity culture. Most beauty products come with wild claims too. Before Sephora, celebrities sold their skincare lines through infomercials. Soap star Victoria Principal (once married to a plastic surgeon) had an anti-aging line called Principal Secret. Supermodel Cindy Crawford partnered with Dr. Jean-Louis Sebagh, a “cosmetic doctor,” on anti-aging line Meaningful Beauty. Kylie Jenner has Kylie Beauty. Hmmm...what is their secret?

Since COVID started, there are more Tik Toks promoting beauty products or demonstrating facial massages and lymphatic drainage techniques to sculpt and depuff the face. There was, and still is, a fixation on “post-COVID bods.” The way we’ve all coped is our business, but I’m especially mindful of which celebrities are trying to capitalize off those coping mechanisms. Cosmetic procedures are becoming more accessible and our increasing access to celebrities—since the early 90s—means that we’ve gotten better at spotting when someone’s had some work done. With enough time, we come to understand what living does to a face.

Rumour Mill:

A Facebook post from August was entertaining (no one has confirmed this!) the idea of a Death Becomes Her remake with the following casting:

Anne Hathaway as Madeline

Kate Hudson as Helen

Lady Gaga as Lisle Von Rhuman

Recommended Watching:

Scott Barnes gives Tati Westbrook (lol!) the “JLo Glow” -- includes that overlined nude lip.

Rupaul’s Drag Race: Season 7, Ep. 6: “Ru Hollywood Stories” (runway theme: Death Becomes Her).

Beetlejuice (1988)

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957)

Eyes Without a Face (1960)

Goodnight Mommy (2014)

The Skin I Live In (2011)

Hirokazu Koreeda’s After Life (1999)

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962)

Recommended Reading:

Some recaps from Jennifer Lopez’s infamous Movieline interview.

Hervé Guibert’s Ghost Image

David Rakoff, on looking for a new face.

Karolina Waclawiak’s Life Events

The Gloriously Queer Afterlife of Death Becomes Her by Kristy Puchko

Kevyn Aucoin’s Painting Faces

Feel free to:

send me your favourite screencaps or suggestions.