“Time is something that scares me. . . or used to. This piece I made with the two clocks was the scariest thing I have ever done. I wanted to face it. I wanted those two clocks right in front of me, ticking.”—Félix González-Torres reflecting on his “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers)

In my last year of high school, a French teacher made the class read Jean-Louis Servan-Schreiber’s Le Nouvel Art du Temps, because she felt we were too worried about time. That concern was a great gesture that predated the internet, smartphones, the Great Recession, and the hustle economy. Yes, there is always a device, app, or something stealing us from the present. Arguably, our workloads skew time perception too. Companies are obsessed with “time theft,” and as a result, workplaces must quantify time to evaluate employee productivity in the office (now at home) or on the sales floor.

The French have a saying — joie de vivre — and you could say they live by it. If you’ve ever had to memorize French verbs, then you could argue that the language shapes the perception of time too. The French have invented literary tenses for novels. They also have the subjonctif, which is meant to express a desire or hint at its possibility. Impératif is for ordering someone around, which can be accomplished in the past or present. The French language is obsessed with the state of an action or desire: completed? Meant to be completed? Might be completed? Satiated? (No wonder “ennui” is part of the vocabulary.) How could that not shape your sense of time and efficiency as a human being? So is Le Nouvel Art du Temps, a self-help book on time management and in French useful? It depends. The only thing I remember from it, word for word, is an off-handed remark from critic Jean-Louis Bory, who is recounted— past tense —as pointing to his watch and telling a friend: «Tu vois cette montre. C’est ma mort.» [“You see this watch. It will be the death of me”. ] I especially remember the parenthetical note from Servan-Schreiber before he quoted Bory, something along the lines of “he said this, not too long before his suicide, to a friend”. What was more staggering was that implied synchronicity. I thought of this remark when I read that Édouard Levé submitted his manuscript for Suicide ten days before his own. Timing, right down to how it’s embedded within a sentence, can make a point. But it can veer towards inappropriate if it comes too soon.

Time management skills can’t contend with fear of unemployment, work ethic expectations, or unpaid bills. Your efficiency as a human being isn’t tied to getting ahead, but making ends meet. You can read Eckhart Tolle all you want, but being present in this economy? I mean literally today, when a lot of people are struggling to survive, make rent, and eat. What could we even say about a job market that, before all this, was segmenting our career decisions and livelihoods into short-term contracts—3 months, 6 months, 1 year—with no health benefits or job security? We’ve all lived many lives, trying to approximate our fragmented work experiences into some edited version of a career. Wasn’t that the lot of cover letters and resumes: to justify gaps between jobs, short-term work, and layoffs? We impose a narrative to suggest that we’ve had a plan all along. Meanwhile, in job postings, time is its own currency: you’re told how many hours a week you’ll commit to work, how many years of experience you need, and where you stand in the corporate hierarchy (meaning whose time is more valuable than your own). Conveniently, the pay is never advertised. Somehow I see the point of networking, how it justifies the hours of small talk: good connections mean that someone else will take on the challenges of salesmanship for you. Either way, someone is tasked with telling the right stories in order to function in this moneymaking society.

I once read that there are two kinds of time: mechanical and human. You could say that my story began at 8:59 the day I started that job and ended months later when I left it. But I’d tell you it began in the past, with my old self; and ended in the future, with the new one. — Iris Chapman, Clockwatchers (1997)

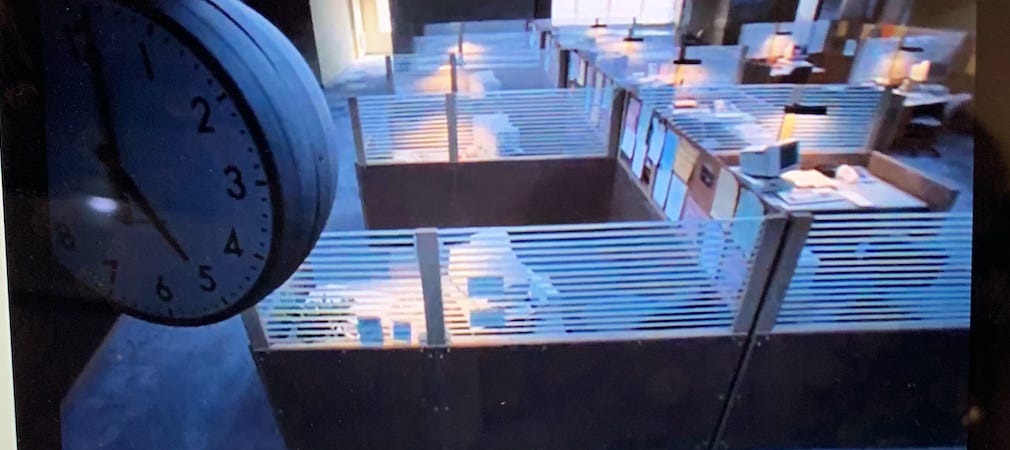

In Jill Specher’s Clockwatchers (1997), which notably predated Office Space (1999) and even The Office (2001), work means numbing stability, which is reinforced by incessant ticking clocks. At work, at home, or during lunch breaks, these ticks sometimes lead to release. In the opening scene, a clock ticks as Iris Chapman (Toni Collette) stands at a front desk, waiting to be acknowledged by the attendant. It’s 8:59 and said attendant is reading a magazine. Tick, tick, tick, and it’s 9 o’clock, which means he can help her, and that the film can start. In another context, at EOD, a group of temps watch the clock until it’s 5 so they can leave for happy hour.

Camaraderie can be an antidote to corporate drudgery, especially when office culture takes up at least 40 hours of your week. That time adds up: all the unreasonable expectations, dress codes, and office politics eventually shift your center of gravity. Suddenly, you articulate your interiority with external markers like raises and promotions because you’re defined by your work and eventually your job. The dumbest things become significant because the best way to cope with the monotony of printing copies, proofing, typing, filing, emailing, faxing, and stapling is to either distract yourself and gossip or develop OCD.

As a team, Iris, Margaret (Parker Posey), Paula (Lisa Kudrow), and Jane (Alanna Ubach) put out fires in the office with little to no recognition. This is part and parcel of life as a temp: you invest time in a company that won’t invest in you. Goals, like fantasies, never materialize. It’s easier for them to pretend they’re needed.

Compared to another women-led office satire, 9 to 5 (1980), Judy (Jane Fonda), Violet (Lily Tomlin), and Doralee (Dolly Parton) daydream about punishing their boss and improving the work environment for women. Their solution is to kidnap him. Iris and her cohort, on the other hand, organize a failed labour strike, as in one person doesn’t show up to work, while the others scab. (The irony of temp workers striking is not lost on me.) They still care enough about the job to mine some meaning from it, but unlike 9 to 5, they don’t confront their boss because bureaucracy gets in the way. There is no direct line to the people they work for, because they answer to middle managers and HR instead. They don’t ruffle feathers because they desperately need this job and know they can be replaced. Consequently, middle management exploits that fear: When Iris is called in to the HR manager’s office to get lectured on hygiene (Iris’ hem has come undone), all it takes is for the manager to suggest that she’ll be fired, and Iris is in tears. She then walks to her desk cowering as she staples her hem and shields her face from the others.

But why should water cooler talk lead to friendship? With all the time they spend together, outside of work, they don’t even seem to realize that they could be friends. Instead, four coworkers simply help each other pass the time. How do you define relationships that result from this forced intimacy, which requires you to spend 40 hours a week, 50 weeks a year with people you barely know? These temps bond by virtue of their expendability, and because none of the permanent hires acknowledge them. All Iris, Margaret, Paula, and Jane can hope for is someone remembering their name long enough to give them a recommendation.

The more they get to know each other, the more they resent the other’s stagnancy. At one point, a psychic tells Iris that she’s tiptoeing through life, not taking control of her own destiny. Margaret always talks about gainful employment and disappointing her parents in most of their conversations. Paula, an aspiring actress, practices her autographs, but never goes on auditions or lands any gigs. And Jane, the consummate perfectionist, is obsessed with planning a wedding to someone who’s cheating on her. Clockwatchers shows that while people can be defined by a job, so too can their friendships. We now qualify those relationships as professional, championing our “work wives”, which, in turn, implies that boundary. You don’t engage outside of work unless you have to.

Eventually, an office thief will alienate the temps even more. The stealing spearheads a string of chaotic events that will tear the women apart, revealing that they’re not on the same page, that it’s time to move on. Margaret will be fired, Paula will get transferred, and Jane will get married (and not invite any of the girls). Iris is left behind to make amends and plot her revenge—all too little too late.

Coincidentally in English, “temps” means temporary workers. It conveys an expiration date on a job. In French, temps means time. In linguistics, words that look the same but have different pronunciations and meanings are referred to as “false friends.”

Growing up means you can’t be distracted anymore, and that you spend less time on interests and more on someone else’s gains. This is what recruiters refer to as team players. When was the last time you were interested in something without interrogating it? Without trying to figure out what you could gain from it? Or did you just trust that the reason would, with time, become clear to you? What my teacher was worried about was not how we were parsing out our days in colour-coded class schedules, but that we were assigning outcomes to time. If anything, things are much worse now, as we’re more overworked than ever. Efficiency, productivity, and ambition inform our every waking hour, even, as we’re learning, during a pandemic.

When Félix González-Torres’ partner was diagnosed with AIDS, he turned to an everyday object to articulate his biggest fear: the passage of time. Both clocks, like two separate lives, are meant to fall out of sync with each other. But the picture of the clocks versus the moving replica, doesn’t quite communicate this. Instead, it’s hard to decide whether the clocks are frozen in time, as if Gonzalez-Torres and his partner have bought more of it, or whether the clocks have stopped. The fear isn’t just the passage of time, but that everyone else, like the hands of a clock, will move on without you.

Additional reading:

Working by Studs Terkel

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber

Nickel and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich

Things to watch:

Fran Lebowitz, on learning how to tell time.

The opening scene of Drive (2011).

Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967)

Clockwise (1986)

Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985)

Thank you for listening:

“Tick of the Clock (Extended Overdrive)”, Chromatics

“The End Has No End", The Strokes

“12:51”, The Strokes

Feel free to:

send me your favourite screencaps or suggestions.

better than Temporary tbqh