Cameron Lee is a Toronto-based costume designer, image maker and DJ whose work has been shown at the AGO, the Power Plant, Mercer Union, Art Metropole, and Erin Stump Projects. Cameron recently designed costumes for films including Close to You (2023) and Paying for It (2024).

I wanted your perspective on costume design because a lot of what you do helps us suspend disbelief in many ways. This all involves glamour too, I suspect because it can involve masks – some much more ornate than others.

Absolutely. I’m glad glamour came into the conversation because it's such a useful tool. Glamour is a Scottish word. It's about magic, and about letting an aspect that you could see become a way to cast spells – either giving an impression or letting something suspend for whatever you need so messages can get across. In both of those worlds, you either see it or don’t because you’re so caught up in your own nonsense. If you see it or recognize something, then there are those of us who can look at each other and say, did you see that?

What does it take to get that nod, to make a look translate? I’m thinking of these celebrities who are obsessed with hoarding archival everything and the final look doesn’t always land.

I respect the dedication to collecting and making authentic head-to-toe versions of all of those archival or true couture looks come together, but looking at those things and actually understanding them means understanding that people made them. There are endless narratives attached to these pieces. What were the people thinking? Who were those people?

What were they giving to what they made? The idea of wearing archival head to toe is…so is that cosplay? Is it wearing a costume at this point? What of you are you bringing to it or giving to that?

I want to dig into this more. So there was this particular Mugler look Kim Kardashian wore on a red carpet. Well, it wore her. When we compare Kim’s Mugler look to Zendaya’s for the Dune 2 premiere, there’s a notable difference, but I can’t articulate it. What makes Zendaya’s work?

That's the end for Kim, right? The clothes are placed on her. She has a lot of money and has invested in her image. And she has a lot of time to conspire to make all of this into a fantasy. But the fantasy is just an image. What is she bringing to it other than being a business person who is rich and has lots of body modification that looks really incredible and fantastic, but is just bland? It's the Courtney Love critique of that Venusian fantasy, this Venusian ideal – what else is it other than itself?

The Zendaya example is interesting. Law Roach did an interview with Recho Omondi and talked about training her to wear a specific Christian Louboutin heel – the Kate – and that specific stiletto is the way that she was trained to carry herself. In interviews, Zendaya says that her conversations with Law Roach are reciprocal, which is great because she wanted to wear that Mugler robot look you brought up. And somehow, based on serendipity, but also self-awareness, it happened to fit her perfectly. That was an uncanny moment. And it feels so much more Mugler-esque than the actual moment when Manfred was making Kim K’s “wet look” outfit, which was too horned in. In order for the glamour to work, it has to be a true Cinderella experience where it’s kismet. As somebody who appreciates and loves camp, because I have to acquiesce to it, you need the camp factor of seeing the strings.

How critical is it for an actor to work closely with the costume designer? I think even about the partnerships between Audrey Hepburn, Edith Head and Hubert de Givenchy, which worked so well on and off screen.

Let’s take a scene from Charade (1963), when Audrey Hepburn’s character walks into an empty apartment, ready to divorce her husband. I have to rewatch this every year. That moment was such a satiating experience. Look, I love The Alps look. It’s so great. But in this particular scene, it's the combination of this humorous levity with this darkness and just the intense rigour of it.

I get the same feeling when I watch Lauren Hutton in John Carpenter’s Someone is Watching Me. It has a comparable air of this kind of interesting, humorous, sexy kind of gamine creature. She's got a distinct style, and she too clearly worked closely with the costumer on that wardrobe because the layer of that is so idiosyncratic but so perfect. These weird smock shirts over top of her suits. Like, it's so great. It's all colour-coordinated. It all comes together every single time she walks into the apartment. I'm like, oh, they found another way to get this, like, pearlescent oyster mixed with a beautiful warm camel and a soft elegant sky pink. She’s smoking and you can see the wrinkles on her, and she's got a little bit of frizzy hair here and there. Just a little like 70s louche compared to the intense perfection of the 60s.

Are actors willing to collaborate with you? Does that work out better in the end?

[Nodding.] Because an actor can then bring the kind of narrative that is built into the wardrobe.

Like what?

Even though you're wearing closed-toe shoes, I know that you have those painted toenails because that's just what your character would do. It’s knowing, from the undergarments to the jewelry I don’t ever see. I know it’s underneath there because you might catch a glimpse of that through a thin knit. That gives it a psychological intensity that makes it feel believable or makes it at least feel like there's humanity to it.

Do actors ever try to wear their own clothes?

Let's say a cast member sees something and falls in love with it, then we have to find a way to work with it despite it causing problems. If this item is too hot on camera, like it's a bright colour visually or print, then that becomes a negotiation process. Could we find one that is less busy, but still does the same thing? Like, one that's not designer and is more affordable?

Does this happen often?

Let's get horoscopic with it: a lot of actors happen to be Leos. I love Leos. And the aspect of a Leo is that there's an element of pride. It’s not exclusive to Leos, of course.

You get to see actors go through so many different stages of transformation. What’s that like as a costume designer – when hair, makeup and wardrobe come together?

I mean – for lack of a better expression – it is drag. Actors come through hair and makeup and costuming. And then there’s all of the lighting and artifice that is very subdued to make this parallel fantasy into a reality, where your expectation of how someone's going to look goes through quite a bit of drag. So the makeup, the hair, the costuming is all very impeccable. The drag of it is so subdued that I guess our mediated expectation of it becomes something that falls to the wayside by virtue of us not noticing all of it. But to be reminded of this in movies where it is more heightened or more…like the edges are acknowledged and articulated…it brings the fantasy back. I'm working mostly in contemporary film and it’s much less fantastical. But to see the end of that kind of process – well, it's absurd. Just the amount of makeup that your average actor is wearing compared to all of us in the crew who look like we haven't slept! We're just there wearing our schleppy utilitarian clothing!

Do hair and makeup ever work against the clothing or scene?

I was working on something recently where the scene was meant to be very solemn. One person is on their deathbed in the hospital, and their partner is mourning at their bedside. The influence one of the actors had in the hair and makeup chair was made more evident than any of us wanted: she had a full beat, glamorous blowout hair, and lots of jewelry. When she landed on set, on the monitor, the entire crew was grimacing. This woman looks like she's about to walk a red carpet. Who the fuck looks like that in a hospital when their partner is dying!!! It’s a complete rupture!

What else is overlooked when sourcing pieces or shooting them? Things that look great in person but awful on camera, etc.?

It often depends on how it will be seen. A lot of people today will be watching things on big screens or computer screens, sometimes even a phone. So I need anything that can convey a message – in terms of costuming – quickly and easily at a glance. If something has a lot of print, is that crucial? Is the print something that would be communicating something that I would want or is that correct? Colour is the same thing. I mean, there are rules of thumb for the hierarchy of a cast. The higher ranking in the cast would mean they're more of a hero and they'll be given a hero item that would be recognizable.

What would that be?

Something like a white t-shirt. Heroes can only wear white because they are the most attractive on camera. Even when they're wearing white, I have to ask an expert to come up with a formula – through experimentation or experiential knowledge – that would degrade that white so that on camera, it won't read as dazzling. If I'm a costume designer, I’m communicating directly with the camera teams, the director of photography and the director, and we'll come to a consensus about which colours they're into, what I have sourced and what I would like to see, and we compromise. We ideally come up with something none of us expected – some awesome X factor that gives more than we'd imagined or gives more than we'd believed was possible.

How much research goes into styling a character?

It's endless trial and error. With a more, let's say, higher-numbered cast member, the frequency that they're seen, every detail is scrutinized to the point of frustration, whether it's colour or fit or, even things like: is this character taking a jacket on and off? Is that right for them, is it noisy? How can we engineer it to make it as simple as possible? There are teams of people who are helping them take that on and off over and over to make a seamless little gesture happen with an undistracted glamourousness. It’s absurd! And the industry's built on that!

I did a movie with Sook-Yin Lee a year ago. This was a film within a film, so I was working with a director who was a MuchMusic VJ on TV (who I watched growing up) and it’s an actor playing her on her first movie set. So, Sook-Yin is directing the person playing Sook-Yin who's supposed to be in this 1960s costume dress on a set, and it's deeply artificial. We filmed this scene at the end of the film schedule because we had to find the perfect dress that would embody our intention of that.

What were you looking for?

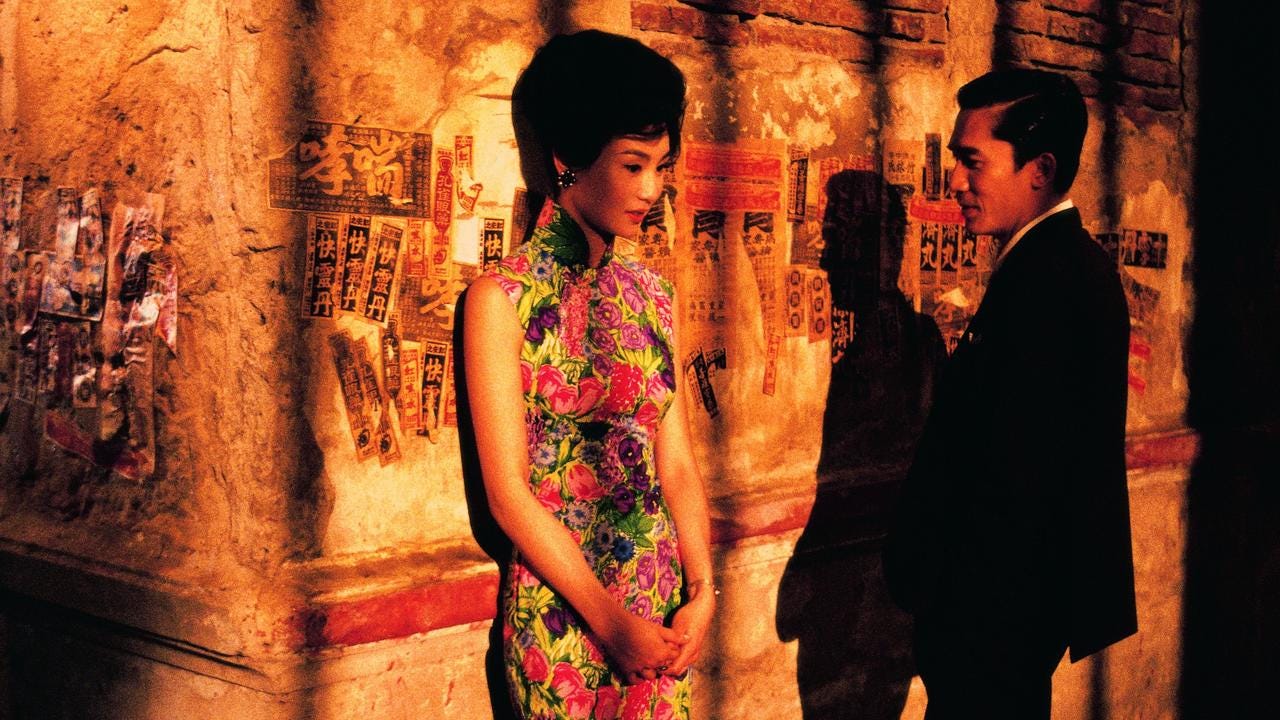

It had to be really stiff and rigid. It's very 60s and so we were looking at Audrey Hepburn films, Mad Men’s distillation of the decade, and then I was thinking about the Qipao from In the Mood for Love. And I was like, will we be able to pull this off? Because I don't know any tailors who could make that level of Qipao. It's hard. You don't have tailors here who have that kind of talent. And through trial and error, we found a lurex, 60s rainbow-on-black Qipao that fit the actor exactly. That was me obsessively going to every rental house, looking at every vintage store, looking at every thrift store, talking to friends who had similar builds and maybe whose mother or grandmother had something in their closet.

I imagine the calibre of seamstresses, tailors and dry cleaners who could care for this garment is also dwindling.

Exactly that. There are a handful of people, and there are other stylists and makers in the city who are very generous. We are all supportive of each other because we have to be. And because we want to share that. I want to be able to share as much of that as possible because when you encounter and appreciate a finely made garment, it's addictive. There's an addiction to truly glamorous and luxurious objects that have their own aura.

How do you make the wardrobe believable? What I mean by that is in horror movies, for instance, a character is really going through it and the wardrobe takes a beating as a result. I imagine there are multiples of each item of clothing. How do you make them look convincing and maintain continuity?

In the film world, there are specific departments (depending on your budget) that work exclusively on breakdown. So the breakdown comes from, either replicating an existing garment or stages of breakdown depending on what happens with a specific sequence. So thinking about Isabelle Adjani in Possession (1981), how many versions of the full dress were there? Of that intense, before and after of her subway tunnel breakdown – she’s wearing that blue dress through most of the movie. I think there was something like 10 for all of the versions of breakdown. I know that somewhere online there is documentation of all of them because that's part of what we're supposed to do. We have to document in order to keep track. And there’s that breakdown we have to account for and an invisibilizing of how we maintain and keep track of every version. We also have the doubles for a stunt double or doubles for stand-ins or we have to find an existing garment and then try to duplicate it. An actor will come in and we’ll find a vintage or rented pair or even their own clothing and then we either try to source another pair or work to make an exact replica of that. That's a lot of fun because all of our faculties are working to make this happen.

I worked on a horror fantasy film under a designer where we had to source 8 of the exact same nylon jackets for all of the various stages of breakdown. So, like, this poor woman is going to go through it where she's dragged into a pond and then climbs through the woods and the jacket rips and tears when she is attacked by, you know, maybe a zombie. So we have all of these phases of this exact same maroon nylon jacket. The sourcing of that was a pain in the butt because we live in Canada where it's harder to find multiples, and we have to factor in things like how it will move, and how it will sound. We had to find multiples for her stunt double who is falling or being dragged into a pond. And then we have to factor in how the jacket will behave when she's moving around in the water and then emerges from it. How will the water evacuate from it?

So you’re saying there was definitely no suede in this jacket. Does this affect shooting in any way?

Yes. I've worked on sets where some people say I love this vintage jacket, and then we're beside a body of water, or an actor has to drink or eat something. And that immediately causes so many logistical concerns. How do we keep this from being destroyed so that we can get as many shots as possible? How can we work around it if there is damage? Like, nope. We can't have any more shots or scenes where we see over their shoulder because it got wet, or she sat down and had a sip of coffee and ripped part of this jacket. It happens all the time. And we have to maintain the illusion for as long as we can.

That's part of the nuts and bolts of maintaining garments throughout a film or a TV show. Then there’s continuity and negotiating personality – so what we’re supposed to be seeing versus what we are. There are all of the ins and outs conspiring to make that happen. A film sequence can be 30 seconds in some cases, but it can take a full 12-hour day to shoot if you're lucky. Let's say, you and I are having a conversation on screen. We want coverage of the 2 of us talking in profile. Then you want coverage from the front, where I'm seeing the camera over my shoulder or from my perspective. And then ideally, we want something where we can get the opposite side of that same thing. So we’re turning the world around. And all of that is just that we can get as many versions of it and catch the best of those. The continuity and consistency is this: Every single time we shoot them, it is consistent in terms of what we see, hear, and what happens around them. And it's often frustrating when someone's not so cooperative, when they're like, oh well, they're not gonna see this.

People get tired, especially of doing the same thing. But that’s the moment you catch something:

Is it okay if so and so doesn't wear their shoes?

Oh, don't worry. They won't see them.

We definitely saw them. And we can’t use that. And now you've just lost 2 hours of footage. And that’s thousands of dollars out the window. And people's time. So everyone has to be vigilant.

Earlier you described glamour as casting a spell. When we were messaging about this earlier, you mentioned watching The Witches (1990) constantly as a child. What drew you to it? How did you feel about Anjelica Huston, playing both a glamorous bitch and wicked witch?

Anjelica Huston has always been an involved fashion icon who’s lived through maybe the more influential aspects of the 20th century. Then she came through to the other side to become not just a glamorous image, but an architect of her own destiny. The Addams Family was such a powerful example: the blending of glamour and of death and darkness with humour and irony. And that feels like the similar seduction that comes from a glamour of Morticia Adams versus The Grand Witch, where you're sort of like, oh she's a diva. To contemporary parlance, she's cunty, and she commands a room, and everyone bows and acquiesces to the diva's whims – even when they maybe go a little bit too far. There’s this camp factor to it, this John Waters-esque moment of like, well fuck it, I’m going to do it anyway. And the magic happens when I'm seeing this beautifully glamorous woman turning, and it's Anjelica Huston, and she’s removing this mask. And then there’s this very grotesque witch underneath who I’m maybe more interested in.

I remember the great relief that comes when the witches free themselves from their disguises – no more itchy wigs, binding footwear or smooth, poreless skin.

Right? They get to untuck in the lounge, so to speak. It also ties in with the observational critiques of Valerie Steele, where she took some of the normalization of the corset – this projection of it being torturous, something that was subjected upon women. But then I think of people like Amanda Lepore, who in many eyes, is a living work of art. I mean, she's Orlan. It's comparable to that mask. We all wear a mask because that is part of our anatomy. There is this protective layer that's also hiding all the mechanisms that keep us together, and there's a grotesque fascination at that being revealed. There's also this inevitability over time, where one has to maintain that mask with surgeries because their image is part of their livelihood. And glamour is also part of the fun of that maintenance.

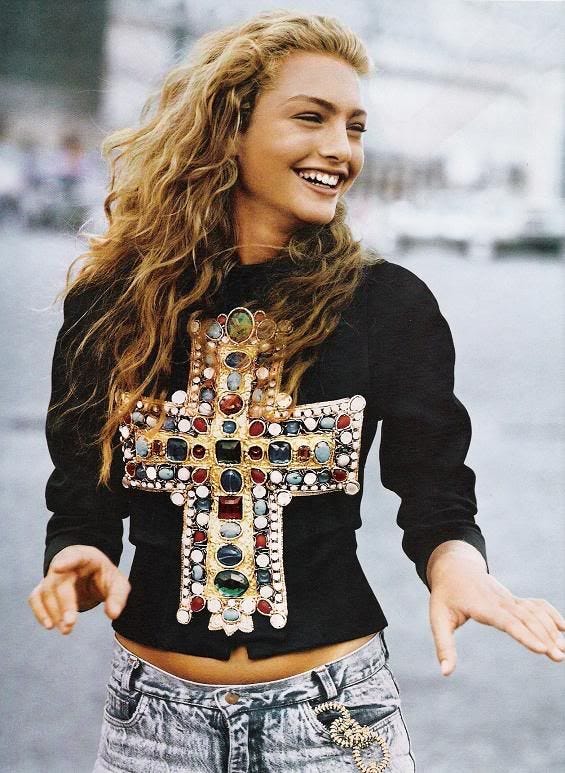

Even bringing it back to Mugler: Throughout his career, he was building these armatures that changed the way you would carry yourself. Incredible. But then the overlooked or overshadowed darker side of that was Claude Montana, who had seen the nightlife sphere and had an element of vampirism. I mean, rest in peace. His influence is much more powerful and present than I think was given credit during his later life. But he was working in the realms of the posits of Cristóbal Balenciaga – of moulding you a second skin that you could live in every day. It wasn't this highly glamourized fantasy. It was the, you know, you can wear this with jeans. It was the mixing of couture with the everyday. Or it was taking the Americanized model of using sports to make it more livable. That kind of glamour is quite remarkable too.

Why?

The extreme glamour of seeing the grotesque witches thereafter is one thing, but then there’s the subtlety of that impeccably dressed witch who pulls up in her Mercedes or just appears in her polka dot look with her little hat and, you know, has these alluring little gestures – to behold her is to kind of gasp at how impeccable she is.

So to you, glamour isn’t something that’s always very intricate or grand – it can be simple and effortless. I think of The Row, how it’s deemed effortless, yet no one can dupe it quite well. There’s tailoring, construction and materials that people overlook. The devil is in the details, you know?

Absolutely. There is a very subtle lineage to that. And I mean, again, it's the Balenciaga of it all, but also, like, the rigour and wit and intensity of Jeffrey Bean and the Olsens where it's a very effortless glamour because it's engineered rigorously. It's scrutinized to the point of frustration. Make a glamour that is perfect, which is: it's seemingly effortless because of the silent story or hidden mechanisms that make it. That's the strangeness of this everyday glamour or this effortless glamour. I mean, whatever – “quiet luxury” is a whole other conversation. I don't subscribe to that kind of narrative. In order for effortless glamour to work it has to be rigorous and obsessive. You have to be obsessed for it to work. Even if there’s something less intense in the structure, it's still rigorously planned, like an Alaïa ensemble. Azzedine Alaïa was somebody who clearly loved human beings. And to look back at just the creative input that he's given dressing in the 20th century is remarkable – right down to a really well-made pair of stretch pants.

I wonder: are there any well-known characters who look understated on screen, but have very exclusive or under-the-radar designer pieces? Maybe something we’ve all missed?

I’ve always felt that Miranda from Sex & the City was an outlier because she's divisive and there are derisive comments about her, but she's also had a lot of remarkable moments. I do remember one item, and at the time, I was so skeptical of it. She's wearing a hat over a hoodie. They're sitting in a park. And then in hindsight, I'm like, that hoodie is the first Yamamoto collaboration with Adidas. It's from that collection. Big deal. Like, this is a powerful item. It's not just a hoodie. It's this, like, tunic that was worn with this bias replication of an Edwardian dress, and now I'm sort of like, Pat Field is a genius.

Pat Field is a great example because, to me, she demonstrates that a costume designer or stylist is necessary for world-building. On paper, Carrie Bradshaw’s life makes no sense and those numbers don’t add up. Who cares? Celebrity stylists are now referred to as image architects. So they have a hand in creating these resonant images for us. I feel like they’re equally pulling from strong film and pop culture references too.

My brain goes through things like the reference point of Brian De Palma’s Body Double (1984) being a source of inspiration for Mel Ottenberg, who was a stylist for Rihanna. And he still has that relationship to fantasy that comes from glamour. He was one of those people who would take a contemporary thing or a menswear or archival piece and end up with Rihanna in a showgirl look with huge earrings and citrine drinking a Corona. Mel was building this version of an assembled glamour based on stuff that he had access to and the conversations he had with her and then he actualized the magic of an archival piece in the present.

Yes, those looks solidified her as a style icon to the establishment especially. I remember her accepting the CFDA Award in that Adam Selman number – when she looked at a reporter and said “Do my tits bother you? They’re covered in Swarovski crystals, girl!” Let’s talk about Body Double for a minute because this is where glamour really casts a spell and fucks with you.

Exactly – you get that moment when you arrive into this world, it's very spooky and dark and glamorous, a little bit sexy and rock ‘n’ roll. And this character reveals themselves to be a vampire immediately hissing at you, looking directly at you. And then you get the “CUT”! This is all artificial. This person's having a panic attack. They're trapped in this artificial world, and they are destabilized by it. So every abyss is about artifice and layers and masks. I'm performing for the audience I'm acknowledging, and now the audience is implicated in trapping this person in a coffin where they will have to escape to maintain their life. And the rest of the movie is going to be about all of these dream sequences and self-awareness sequences of people performing for a camera and then for each other, or for us. It’s really a fantastic, solipsistic, Giallo goofball narrative. Glamour can trap you if you aren't clever and quick.

You have to have your wits about you at all times.

Yes because that glamour can quickly turn on you when you are at your most vulnerable. We have that with Body Double – of being so enamoured by someone. There are a number of realms dealing with the nuts and bolts of working as a sex worker, how that actually feels as someone who's a practitioner versus the fantasy that's projected on by a client.

Right, the idea of building a relationship out of something transactional. And Hollywood operates that way – it’s very transactional between actors and the industry. But then fans project an image or fantasy onto a celebrity too. A celebrity can’t exist without Hollywood or the fans.

The cat and mouse of both worlds. The two moments in Body Double when we really are drawn into the glamour, it’s reflected harshly back on us. He's a vampire in this amazing perspex, fake but underground coffin. You're really given the tropes of Hollywood and that is quickly pulled away from you. And then when he's with Melanie Griffith and they're in this music video, you wonder, is this porn? Is it a music video? Is it actually happening? And then we catch the glimpse of a door closing and the film crew that is reflected back to us. So it’s not just the facade of that facade. We are implicated in this, in that, goofy Hitchcock way: You wanna see this film, don't you, you pervert?

And to circle back to your observation earlier about this head-to-toe archival obsession – it can trap you in the past. Or you can trap yourself there by trying to maintain its vitality – where you’re this hyperbaric chamber, trapped in this perspex coffin where it looks cool and glamorous, but there is no room to grow. There's no air in that. It's still a coffin.

Like the status of this mining of and then this internalized echo chamber of archival dressing and how we engage the magic, and by magic, we mean the hard work that comes with researching and developing and learning a physical trade through which you will garner that.

Yohji Yamamoto's whole career has been built on his reverence for Edwardian everyday clothing and couture clothing that actually is lost. So what can we do to maintain that fascination? And I mean that for Margiela too. He was like look at this stuff that I'm finding at flea markets. You can't make this anymore. The mills don't exist. And the textiles can't exist because they were made with toxic substances that will make you a mess.

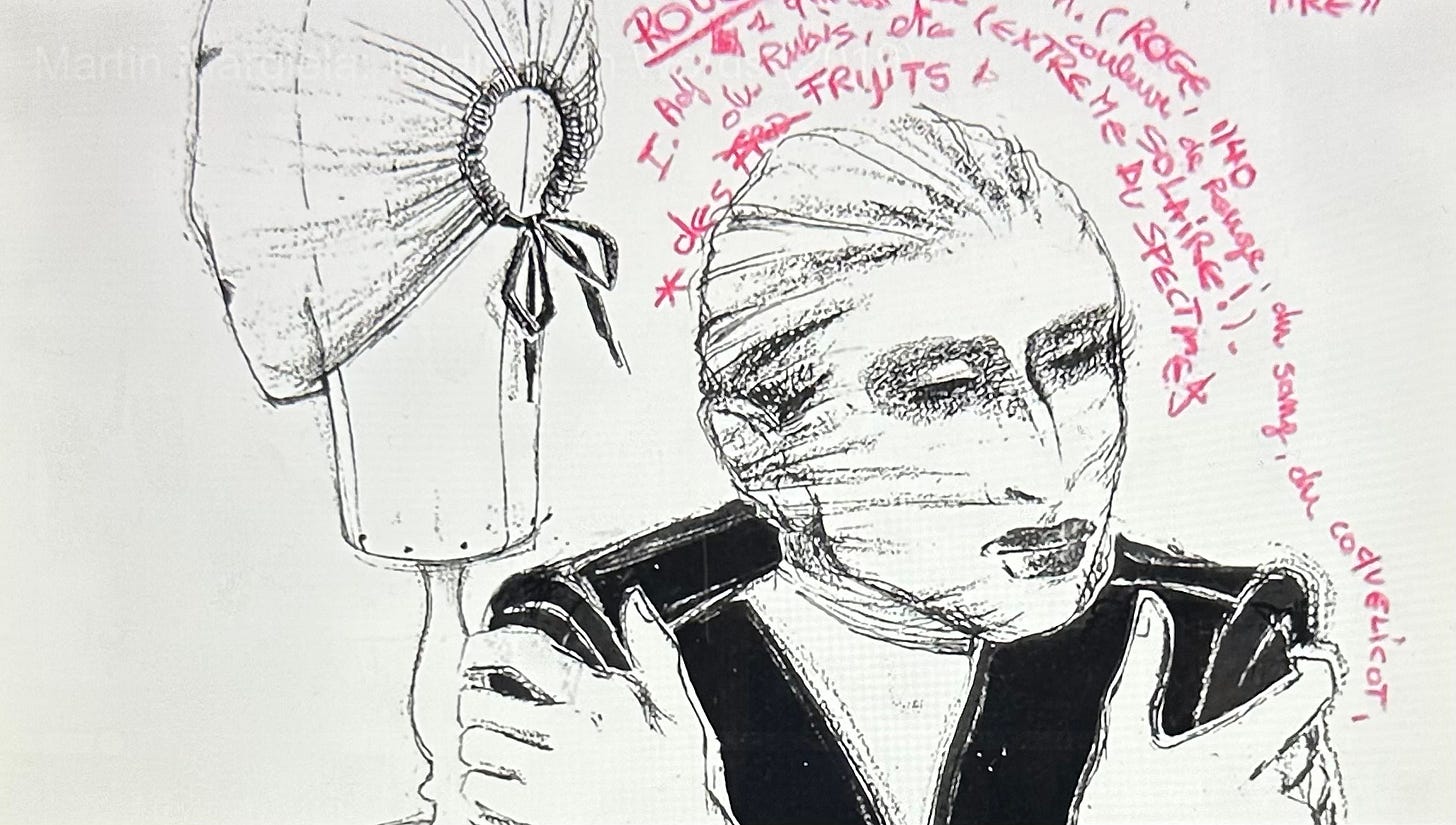

In his documentary, which I really love to rewatch, Martin Margiela: In His Own Words (2019), he talks about his couture collection where he was doing these studies, and then realized partway through that the resolved versions of that were just boring and dead. The interest comes in this process of discovery, about looking deep into the history books to remember that there was a living, breathing, desirous person making stuff in the past, and they have a lot to teach us. There's vitality.

What else have you been watching lately? What other worlds are you immersing yourself in?

There's this very camp documentary from the late eighties called Haute Couture: The Great Designers. It's about this French couturier in the late eighties, and there's a pretty great conversation between Carrie Donovan and Grace Mirabella and they’re just waxing. Waxxxxxxing! It's wild – some of the hyperbole he gets into wearing all white, talking with the couture clients, and then this researcher at the Sorbonne, and she's talking about the genteel past that we just don't have anymore. Women in particular don't have the time to have someone make a custom garment, like, that would have necessitated all of these couturiers and all of these specialists.

And we want those things because they're rare and because they're fleeting and because there's an exclusivity to it and even this approach to archival means more like hoarding than it does of a practice. People collecting stuff and then bragging about their hoards. I'm not gatekeeping, they say, I'm sharing the information. It's like, well…I mean, it would be so incredible if those billionaires who are so concerned about their appearance and their hoards would invest back into the grand kind of industries that once made all these beautiful things. Invest back in Lesage, please.

Lacroix, too, while we’re at it.

YES! Lidewij Edelkoort, the Dutch social theorist, was talking about this. She was saying these big conglomerations need to invest back into building community spaces too. There has to be social investment put back into people without any expectation of a financial return. Otherwise, the illusion will implode, and humanity will be lost by virtue of it being just about statistics and numbers. And I think one of the examples that came up in these interviews with Edelkoort was Burberry, which is hilarious now that it's crumbling. She was saying there needs to be the Burberry building, and all they do is put their name on it. It's a community space, and they do not touch it. They put money in that and we revere that as this monument of social space and it only exists by virtue of the exterior. Anything that happens in it is up to those who participate in it, and they foster whatever they're going to foster uninterrupted.

Is this about putting money back into the communities where the workers live, grow up, etc.?

It’s about how we engage the hard work that comes with researching and developing and learning a physical trade through which you will garner that magic – the same one that has helped create all these archival pieces that are being hoarded. They only exist in an echo chamber. Yohji Yamamoto's whole career has been built on his reverence for Edwardian everyday clothing and couture clothing that is actually lost. So what can we do to maintain that fascination? And I mean that for Margiela too. He was like look at this stuff that I'm finding at flea markets. You can't make this anymore. The mills don't exist. And the textiles can't exist because they were made with toxic substances that will make you a mess. But what are we doing to shift that into a new way of looking? I don't know.

What I know is that we need small-scale and local again. Bring it back to its basics and its roots. Because the further away we are from it, the more of a facade and the more of an artificial replica it becomes. And then we're left with these hovering illusions that are iterative and meaningless.